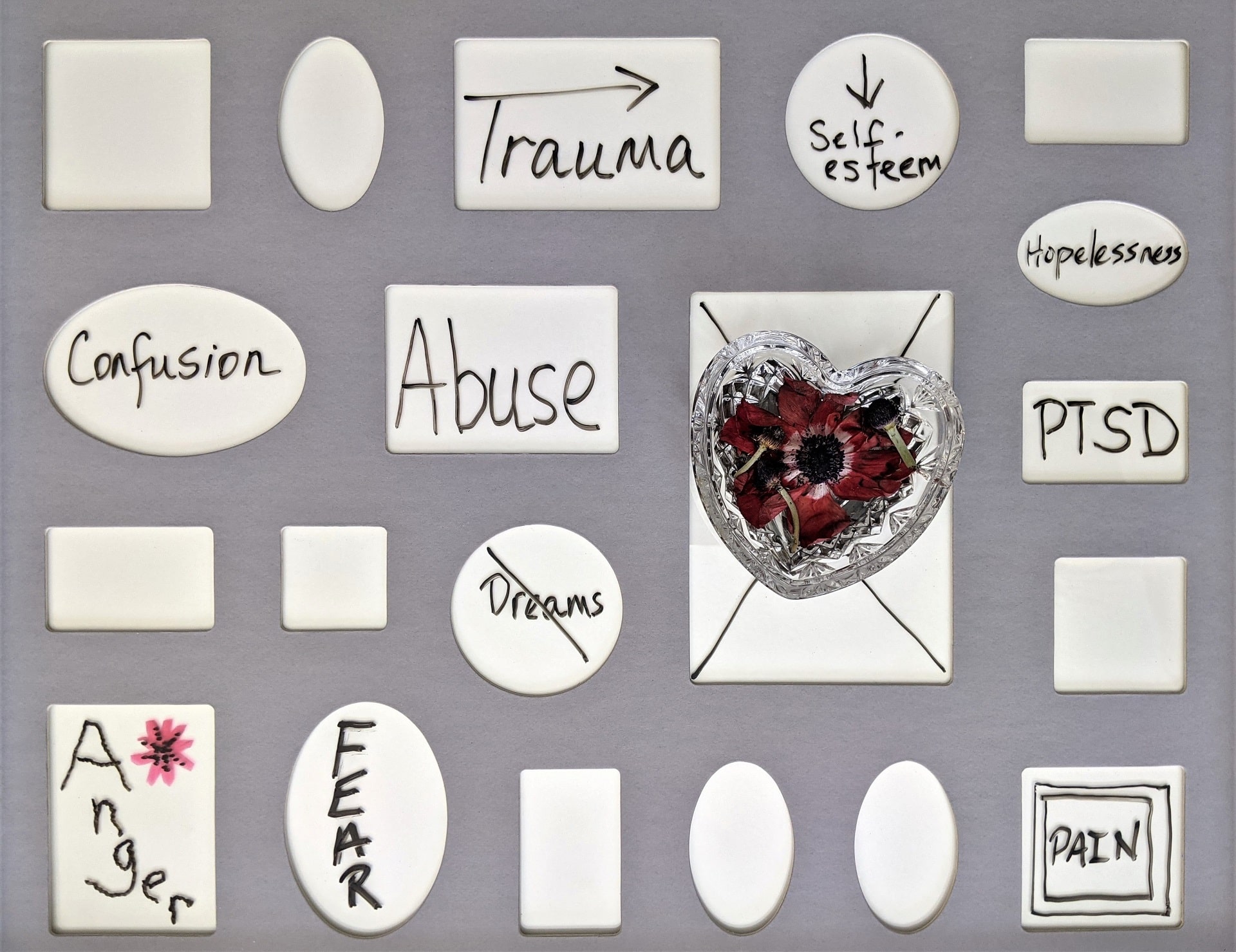

For a long time now, our society has had a tendency to medicalise people’s misery. We have looked at suffering, and drawn a conclusion that people who suffer emotionally must be ill. Just writing that, it seems implausible. Implausible that someone loses a child and we can diagnose them with persistent complex bereavement disorder, or that someone witnesses or experiences a horrific crime and we call them disordered when they have post-traumatic stress. Implausible that we don’t label the thing they witnessed or experienced as disordered. We have it so backwards, and it means we lose our compassion for people and the amazing fact that by suffering, we are simply showing the beauty of our humanity, as well as our capacity for love. This latter sentence may seem bizarre but that in itself demonstrates why a paradigm shift is desperately needed.

1. The beauty of our humanity is lost in the current paradigm

Often when I am sitting with a patient, and they are in deep suffering, I am in awe of them. I am in awe of their capacity to love and their capacity to feel. Sitting with a depressed patient, I do not experience the individual as ill. I experience them as deeply loving and in suffering as a result. For example, I have patients who were abused, neglected and/or tortured and consequently they live life in fear of connection and attachment. This seems rational, predictable and logical considering their experience. They often go about the world in a depressed state, and how do we understand this depression? Do we medicalise it, or can we see it as a state they needed to go to survive their early life. All of us are born with an instinct to attach to our caregiver and we do this via our love. We do whatever we can to maintain this attachment. We depend upon this attachment to survive. When the attachment figure is the abuser, it does not pay for us to express anger, it pays us to spare the loved figure our anger so we can maintain the relationship. Instead we learn to turn the anger inwards on ourselves. And consequently, what should be “they are bad” becomes “I am bad.” There is a sadness in this, and a life of suffering ahead, but when looked at in a non-medicalised fashion, there is also beauty and strength in this. The individual has such a deep love for the attachment figure that it spares them their anger, and instead turns it on themselves. Witnessing this “gift of love” is truly awe-inspiring and demonstrates the internal strength and capacity of the person I am working with.

In therapy, we have to heal in love what was damaged in love, and to truly do this, we need to be able to see people’s suffering for what it actually is, and that is very simply — just a human response.

2. We lose sight of what we all share

If I had to sum up in one sentence the reasons for most of the “mental health problems” or suffering that I see it would be something like this: “all of us, to a certain degree have had to cover up, that which could not be loved.”

What this means is that, from the moment we are born we are given both overt and covert messages about what is acceptable and what is not acceptable by our caregivers. This can happen in obvious ways such as via neglect, or abuse and less obvious ways by avoidance of your loved one’s painful but necessary and important emotions. A simple example of the latter would be my reaction to when my little boy is crying. I find myself naturally responding to him by saying “Shh Shh, don’t cry.” Why am I doing this? He probably has a good reason to cry, and yet even at this early age (without any ill-intent), I am letting him know my anxiety cannot handle his crying. I do this out of love, of course. I am anxious he is upset and I want to soothe him, but I could just as easily say “I am here, there, there. I am here.” Of course, I am not suggesting we should not say “Shh Shh” to our children. Rather, I am giving an example of how our anxiety about our children’s emotions can cause us to react unknowingly to their important and necessary emotions. When this vital part of ourselves, our internal compass, is disallowed or disapproved of, they are shut down and repressed, and this leads to symptoms, and these symptoms lead to a collection of symptoms and these collections of symptoms are labelled a diagnosis, and this diagnosis becomes the problem, rather than the thing that led to the symptoms in the first place. In the current mental health paradigm therefore, we end up treating the symptoms related to the diagnosis and then people wonder why patients in mental health services rarely recover. By doing this and allowing this model to be so accepted, we also sadly lose perspective of what we all as humans share and experience in our lives and that is a society that often means well but has a dramatically impoverished capacity to tolerate our complex and painful emotions.

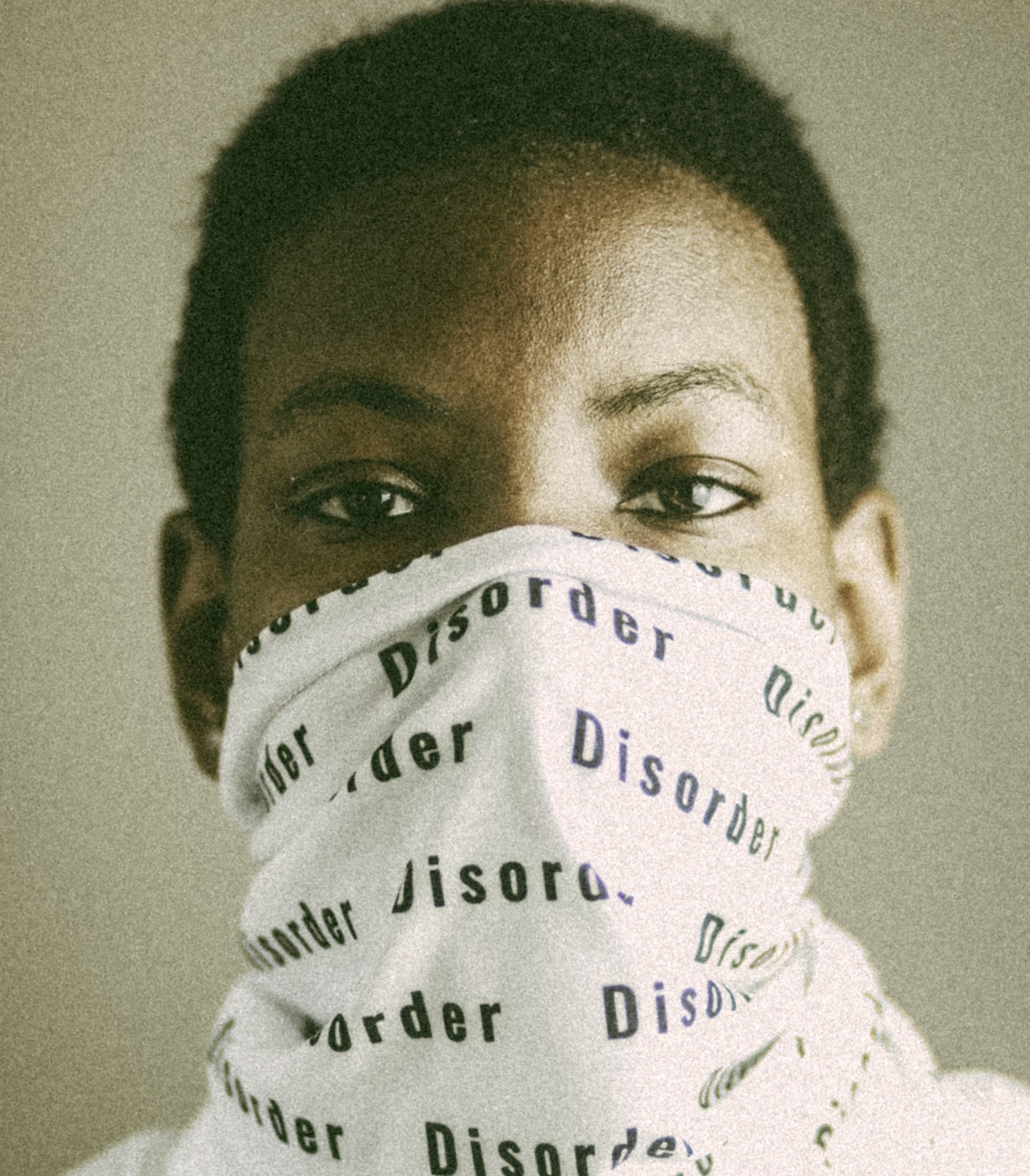

3. We label disordered that which is most human

A solider returns from war, after witnessing the worst of humanity. On arrival, he finds it hard to acclimatise to civilian life. He experiences flashbacks, nightmares, increased startled response, avoidance of anything related to his experience. There is overwhelming guilt and a desire to distract via destructive means. This is labelled as abnormal, and the individual is seen as disordered. What he was sent to do, and witness is not labelled as disordered — he is labelled as disordered. I would argue his response is clear evidence that humans are not supposed to see such atrocities, and his response is his humanity, and his love for his fellow man. And yet, we call him disordered.

How we have got this so wrong? People may point to the fact that some people experience what he experienced and are fine or have limited issues. To these, I would ask — and who are you more worried about? The man who sees atrocities with limited impact on the self, or the man who sees such atrocities and is so impacted it shifts his whole belief system about himself, the world and other people and whose emotions are so overwhelming in response to something that is so overwhelming, he is overwhelmed?

Reactions to trauma are of so much interest, because in reality, all the patients we see have suffered some form of neglect, abuse and/or loss and consequently are traumatised. That is why they suffer, and that is why they need assistance. They are responding as humans should to their experience. The last thing I want to do is label them as unhealthy, ill or disordered. In my view, they are the most healthy, loving and inspiring individuals I have the fortune to spend time with, every day. This does not mean their suffering should not end, it just means their suffering is a healthy response to an unhealthy experience or experiences. Does this not seem more plausible than the alternative?

Without changing the paradigm, we fail to see the beauty of our humanness and perhaps even more importantly we fail to see how we impact on each other and thus how each of us can begin to change to create a more compassionate and emotionally tolerant society.

Dr David Spektor is a clinical psychologist. He’s the director of Psychology Care and a lecturer at the University of Melbourne