Emotions hold intelligence and wisdom, but we often fail to listen. This is particularly true for those in the health care profession and first responders, whose daily lives are filled with unimaginable stress and hardship. These individuals are frequently and consistently exposed to pain, suffering, and trauma, making it a monumental task to keep their hearts open amidst the chaos.

It was Ram Dass, who I first heard refer to the concept of “keeping your heart open in hell” and it speaks to the struggle of maintaining compassion and empathy when faced with relentless adversity. For health care professionals and first responders, this struggle is all too familiar. The demands of their work can erode their emotional well-being, leading to burnout, compassion fatigue, and a sense of detachment.

Many enter these professions with a profound sense of compassion, driven by a desire to help others. Yet, the harsh realities of their work can dim that compassion, leaving them feeling overwhelmed and emotionally drained so that at best, they are professionally warm but internally detached and at worst resentful of the people they care for.

So, how can these individuals keep their hearts open amidst such challenging circumstances? It’s not easy, but there are ways to nourish the soul and maintain emotional resilience. Now most people at this point would expect me to talk about self-care, but there is no use in talking about self-care when most people do not understand what it is. People who advise things like taking a walk, doing exercise, mindfulness, yoga, speaking to friends etc.. mean well, and yes these are undoubtedly helpful, but nowhere near enough, and act to minimise the severity of the trauma health professionals and first responders suffer. Self-care is also not what people think it is. Self-care is not a pleasant distraction from pain, which many of the above activities are used for (even mindfulness). Self-care is in reality allowing the wisdom of your emotions to surface despite the pain they cause and also despite the yearning to avoid the vulnerability that showing this pain inevitably brings. Self-care is building your capacity to feel the emotional pain you have experienced and at the same time building your capacity to do that in front of other safe people who care for you. The only way through emotional suffering is to go deeply into it and out the other side, and doing this is you being caring to you, hence self-care.

Emotions are our internal compass, and through the wisdom they offer, they can guide us on the right path to always keeping our hearts open. For health care professionals and first responders, this means recognizing and honouring their own emotions. It means allowing them to feel and process their emotions rather than suppressing them. After all, our feelings are what makes us human, and for many health care professionals and first responders it was their emotions, the compass of their humanity, which served as the calling to their chosen profession. The problem is that whether you work for the police, or military, are a paramedic, doctor or allied health professional — none of these professions train their people in the self-care that I have outlined above. Instead, while they may pay lip-service to self-care they often do the opposite and treat vulnerability as weakness. This is why we hear so much about staff burnout, stress leave,PTSD and even suicide amongst our carers and first responders.

Imagine a world where health care professionals and first responders could fully embrace their emotions. Love would be deeply felt and expressed, even in the most trying times. Joy would be celebrated, providing a necessary counterbalance to the sorrow they witness. Sadness would be acknowledged and honoured, allowing for healing and emotional release. Anger would be recognized as a signal of injustice or mistreatment, prompting healthy assertion and boundary-setting. Guilt would be seen as an indicator of their inner goodness, guiding them towards corrective action.

This is the intelligence and wisdom our emotions hold. By becoming acutely aware of how emotions manifest in their bodies, health care professionals and first responders can use these signals to direct their behaviour towards appropriate action. Feelings are called “feelings” for a reason — they are felt in the body. A hollow stomach may signal guilt, a sore chest may signal sadness, and tense shoulders may signal anger. These bodily signals provide the intelligence needed to navigate their emotional landscape. But what training in real self-care do any of the professions that most need it receive? None, as far as I can tell.

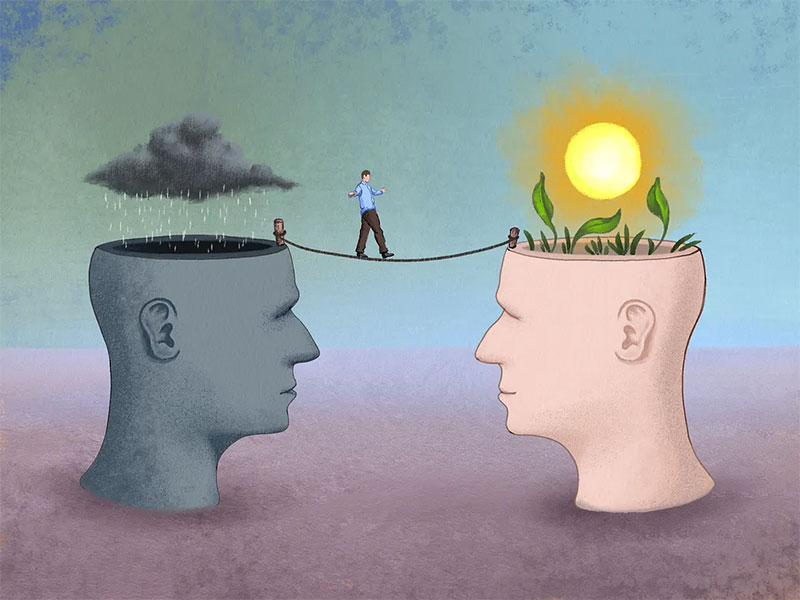

Much of the work in therapy involves helping individuals experience and embody their feelings, recognizing the anxiety that attention to these feelings can cause. For health care professionals and first responders, their symptoms of suffering (PTSD, depression) often derive from actions taken to avoid the anxiety their emotions bring. The intelligence within their emotions may reveal hard truths or vulnerabilities they have learned via their workplace to suppress. But if this intelligence is listened to, it can lead them out of darkness and towards the freedom to love and care deeply once again and be true to themselves. It can keep their heart open.

The challenges faced by health care professionals and first responders to keep their heart open in hell are immense and perhaps even insurmountable for most. Yet, with the right support, real self-care training, and a commitment to emotional well-being from themselves, their community and most importantly their workplace, these individuals can continue to provide compassionate care and support to those in need. Let us honour their dedication to others and resilience and strive to create a world where empathy and compassion can thrive, even in the darkest of circumstances. We owe these wonderful people, who are with us in the hardest of times, at least that.

Written by Dr David Spektor, Clinical Psychologist, Director of PsychologyCare